| Length: 50 inches | Wingspan: 85 inches | Seasonality: Migrant |

| ID Keys: Large size, white body, black wing tips, reddish bare skin on crown | ||

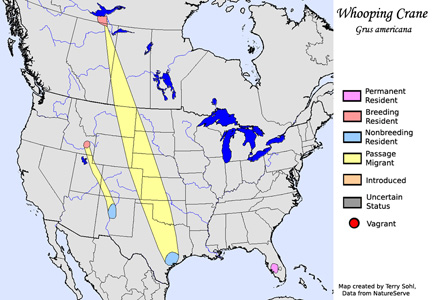

Whooping Cranes were one of the most endangered birds in North America by the mid-20th century, with only 21 wild birds left by 1941. Strict protection has brought numbers slowly up, with over 500 now in the wild, and nearly 300 in captivity. They are heavily reliant on one wintering ground and one summer breeding ground, as over 80% of the wild population breeds at Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada, and winters at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in Texas. Over the last few decades, attempts have also been made to establish resident or migratory populations in Louisiana and Florida, with mixed success.

In South Dakota Whooping Cranes are but (very) rare migratory visitors. They are most often found in the center part of the state and often are accompanying migratory Sandhill Cranes.

Habitat:

Sloughs, marshes, and fields on its migration through the state. As with the Sandhill Cranes that often serve as their migration buddies, Whooping Cranes will often feed heavily on waste grain that's left in fields after harvesting. On their summer breeding grounds in Canada, the habitat is a mix of glaciated pothole wetlands, interspersed by areas of slightly higher, wooded land. On their primary wintering grounds in Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, they are primarily found in and around estuarine marshes and adjacent tidal flats.

Diet:

Omnivorous. Summer diet not well known, but eats aquatic plants, acorns, seeds and grain, insects, crustaceans, frogs, snakes, and fish on its wintering grounds in Texas.

Behavior:

Forages both on land and in shallow water. In water, forages by walking slowly and grabbing food items when spotted, or occasionally by standing still and waiting for fish and other prey items to approach. On land, walks slowly across the landscape.

Breeding:

Currently a non-breeder in South Dakota. However, historically they used to nest nearby in eastern North Dakota and western Minnesota. It is likely they used to nest in northeastern South Dakota prior to European settlement, but the nearest nesting locations now are far away in Wisconsin. On their breeding grounds, the nest of a Whooping Crane is a large mound of cattails and other wetland vegetation often bound with mud, built by both the male and female. The nest may be up to 4 or 5 feet in diameter, and is typically placed in a protected or hidden location amongst wetland vegetation. The female lays 1 to 3 eggs, with both parents helping to incubate them. The young hatch after about 33 days. Whooping Crane pairs mate for life, and typically return to the same general nesting locations year after year, although nest sites change.

Song:

Loud, carrying ker-le-loo, and loud honking.

1Click here to hear the call of a Whooping Crane, recorded in Florida.

Migration:

Largest wild flock winters on the central Texas coast at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge and summers in Wood Buffalo National Park in central Canada. As noted below, a flock is being "taught" to migrate from Florida to Wisconsin in efforts to expanding breeding populations so that the entire species isn't so reliant on the Aransas population. Attempts were made to establish a non-migratory flock in Florida but those efforts have been stopped. Whooping Cranes tend to have very strong fidelity to both wintering and nesting sites, and with overall populations dangerously low, those tendencies are a danger because the remaining birds tend not to seek out and colonize new areas.

In migration, they are never found in high numbers. Single birds or pairs are often seen accompanying migrating Sandhill Cranes, or they may migrate alone. It's rare to see more than 7 or 8 Whooping Cranes migrating together as one flock.

Interactive eBird map:

Click here to access an interactive eBird map of Whooping Crane sightings

Similar Species:

If seen well, Whooping Cranes are unmistakable. Their very large size and white overall plumage make them quite different than other large wading birds. At a distance or if not seen well, they could perhaps be confused with the following:

- Sandhill Crane - Whooping Cranes and Sandhill Cranes often associate with each other, and Sandhill Cranes are only slightly smaller than Whooping Cranes. However, the coloring is quite different, as Whooping Cranes are predominantly white with black wing tips visible in flight. Sandhill Cranes are primarily a warm gray and rusty color. Sandhill Cranes in flight may appear "light" in coloration when viewed from underneath, but they lack the obvious black wingtips of a Whooping Crane.

- Great Egret - As another tall, predominantly white bird, Great Egrets could be confused with Whooping Cranes from a distance. However, Great Egrets are substantially smaller, lack the reddish markings on the head, have a bright yellow bill compared to the darker bill of a Whooping Crane, and lack the black wingtips of a Whooping Crane (seen in flight).

- Great Blue Heron - The plumage differences make it easy to tell apart a typical Great Blue Heron and a Whooping Crane. However, in Florida (and occasionally elsewhere) an all-white form of a Great Blue Heron can be found. They are large, tall wading birds like Whooping Cranes, but have a yellow bill (dark bill on a Whooping Crane), have yellowish legs (dark on a Whooping Crane), and lack the black wingtips of a Whooping Crane (seen in flight).

Conservation Status:

Still seriously endangered, but populations are slowly and steadily increasing, with the total wild population now well over 500. In 2018 the population that overwinters at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in Texas hit an all-time high of 505 individual birds, double the number found just a decade earlier. Efforts were also underway to establish a migratory flock in Wisconsin as insurance against the possibility of a major event wiping out the only existing migratory flocks. Young of the year were taught to follow an ultralight aircraft from the summer grounds in Wisconsin to the wintering grounds in Florida. This program has met with some success, with some birds returning on their own to Wisconsin in subsequent years. From 1993 to 2004, efferts were also made to establish a non-migratory flock of Whooping Cranes in Florida. Nearly 300 birds were released during that time frame, but they birds never thrived or reproduced well, and the decision was made to stop releasing new birds. Efforts have also been underway recently to start a breeding population in Louisiana. Overall, only the Texas/Woods Buffalo National Park flock of birds is a self-sustaining wild population of birds. Other populations have been reliant on augmentation or establishment based on captive-bred releases. Overall, populations are still at risk, given the reliance on one breeding and wintering ground for a majority of the global population, and very small overall numbers. The IUCN considers the Whooping Crane to be an "endangered" species.

Further Information:

2) Audubon Field Guide - Whooping Crane

3) International Crane Foundation article

Photo Information:

September 2010, taken at Calgary Zoo - Public domain photo obtained through Wikipedia Commons.

Audio File Credits:

1J. Frank Goodwin, XC329823. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/329823.

| Click on the map below for a higher-resolution view |

|

| South Dakota Status: Rare migrant. Most sightings have occurred in central South Dakota |

Additional Whooping Crane Photos

Click for higher-resolution photos