INTRODUCTION

|

| Broad-billed Hummingbird on her nest |

As a photographer I'm still learning. All photographers are continuously learning. However, as I said elsewhere on this site, photographing birds isn't rocket science. The biggest problem you typically encounter isn't your equipment. The greatest difficulty is generally getting close enough to a bird to actually take a photo. Most of my tips below deal with putting yourself into a position to get a good photograph, but I'll also provide some tips on camera settings and the like. Here are a few tidbits, and hopefully you can learn a few tricks for getting good bird photos. First, some overall comments:

BIRDING FIRST, PHOTOGRAPHY SECOND

First and foremost, you should always be a birder first, and a photographer second. What does this mean? The best way to be a good bird photographer is to know your quarry. The creation of this website, for example, has made me a better bird photographer. Why? Because by creating the individual species pages, I've learned about the different habits and characteristics of birds. I would almost suggest going out several times without a camera before trying to photograph birds. Take the time to learn the species in your area, their favorite habitats, what time of year to expect them, and how they behave. Take the time to read through your birding field guides and other books. Most importantly, GET YOUR BUTT OUT into the field! Nothing is better to improve your skills as both a birder, and as a photographer, than personal experience.

Keep a Low Profile

This goes with the previous statement. There will be many times where you have the opportunity to put yourself into position to get a great bird photo, but at the expense of trampling habitat or scaring off every living thing within a quarter mile. Any action which helps degrade habitat, endanger birds or other animals, or goes against established laws is an action you shouldn't be taking. Taking photographs of nesting birds is one type activity that will get you in trouble. The last thing nesting birds need is some dude with a camera sticking his nose into a nest site. I have thousands upon thousands of bird photos stored on my hard drive, of over 400 species. The TOTAL number of nest photos I have? Likely 50 or less, and they're only taken in "safe" situations. For example, the Broad-billed Hummingbird shown here was nesting on a vine RIGHT by the entrance door to a wonderful B&B we stay at in Tuscon, Arizona. She was extremely used to people passing her at very close range as they entered or exited the B&B. It was one of those rare situations where it was "safe" to take a nest shot. Overall though, I rarely even attempt it. Here are some general things to AVOID when photographing birds:

- Don't upset the birds. Avoid nest photography unless you can be absolutely sure you're not causing harm to the parents or their chicks. Sure, it's tempting to try and get that great shot of a mother feeding her chicks or incubating eggs. However, that's generally very difficult to do without upsetting the birds themselves.

- Don't approach endangered or threatened species for the purposes of photographing them. Unless you have a good, long lens and can photograph them from a safe distance, you shouldn't attempt to get close to an endangered species just to get a photo.

- Restrict or eliminate the use of bird calls. I'm amazed at how often you come across birders in the field who are calling in birds with recorded songs on their cell phones. These can be either courtship songs in an attempt to attract a bird, or tapes of predators, which can arouse a defense instinct in many birds. Using a taped call not only disturbs the intended species you're trying to attract, but also could attract predators. It's a tempting tool to use, particularly in bird photography where getting close to a bird is paramount. Use sparingly, or not at all if you can.

GETTING CLOSE

Even with a long telephoto lens, a bird photographer still has to get relatively close to the subject, especially if that subject happens to be something like a little 4 1/2" wren or other small bird! How does one do this. I'll say it once again...patience and persistence is free and can often compensate for equipment that is a little lacking. Even if you DO have the best equipment in the world, you won't get many great bird photos without patience and persistence. There are several methods that can be used to get close enough for that great shot:

Stalking

Many species of birds simply do not tolerate the presence of human beings very well. It's not a common situation where you can walk right up to a wild bird and take a photo from a close distance. Can you "stalk" (approach) a wild bird for the purpose of taking its photo? Yes, you can. Patience and a calm demeanor will go a long way when stalking a bird. Some things to keep in mind...

Different species show wildly different tolerances for a human presence. For example, in my area it's MUCH easier to approach a Ruby-throated Hummingbird than it is an American Kestrel. Some species are simply "tamer" than others. One thing I've learned is that individual birds can act differently than the "norm" for that species. My ability to photograph an American Kestrel is a great example. I see them all the time, at all times of year, but particularly spring through fall. The typical sighting consists of me seeing the bird, and that bird flying when I get within 100 yards of it. One morning I was driving along running errands but had my camera along. A gorgeous male Kestrel was sitting on a fence post, and to my utter surprise, he stayed still and let me take a number of great shots. You NEVER know when a bird may decide to cooperate!

Stay readily visible when stalking. Alright, I know this seems counter-intuitive. However, let's face it, our ability to really "stalk" and hide from a wild creature is pretty limited, and you can generally be pretty sure that unless you're 100% concealed, a wild bird is going to be aware of your presence. Approaching a wild bird while trying to stay concealed is very similar to predatory behavior, and birds will react accordingly. Staying out in the open, remaining visible, and letting the bird track your movements will help it realize you're not a threat. Move slowly, and erratically. Don't approach the bird head-on in a steady gait. I will often stay low, move a few feet at a time, sit and wait a bit, move a few more feet, etc. It often works, if you're patient and try to show the bird you're not a threat.

To be honest...how effective is stalking a wild bird? It does work sometimes. But more often than not, a bird will perceive you as a threat as you approach it, no matter how careful you are. The following methods of getting close to a bird are definitely more fool-proof.

Using a Blind

The opposite of the open stalking approach, this approach does attempt complete concealment. The "best of the best" of my photographs are usually those where I'm using some form of concealment, where I'm able to get extremely close to the bird because the bird is unaware of my presence. Not only will you likely be able to get closer than you would by stalking, but you'll be able to photograph natural behavior, without any of the stressed behavior that may occur if a bird senses your presence. There are three kinds of blinds I typically use:

|

| Bufflehead male, taken from a blind |

Permanent Blinds - With the increasing popularity of birding, the availability of permanent blinds in key locations is gradually increasing. Many parks and other government owned areas have permanent blinds built in locations that provide wonderful photography opportunities. Did you ever have the urge to photograph Sandhill Cranes on the Platte River in Nebraska/ An entire cottage industry has been created that caters to birders and bird photographers. Even private land owners in key areas now rent the use of carefully placed blinds. In my area, I have an extremely hard time approach waterfowl, not a surprise given how heavily they're hunted. However I have some truly wonderful, very close waterfowl photos taken from a permanent blind at "Dewey Gevik Nature Area" west of Sioux Falls. Outside of that blind? I couldn't get within 100 yards of most ducks. In the blind? I often have ducks behaving normally, feeding, and even courting within mere feet of my camera lens as I hunker down in the blind. The gorgeous little Bufflehead male photo shown in this section was taken from Dewey Gevik's permanent blind. He approached within 3 feet of my waiting camera at one point, too close to focus, as he courted 3 females in the area. There's absolutely no way any human being could get that close to a wild Bufflehead duck without such a concealed location.

Mobile Blinds - I have a mobile blind in the back of my pickup nearly all the time, particularly if I'm out birding. It's a "chair blind", a little folding chair with a camouflaged cover that you pull over the top. It has several openings you can zip open and shoot photos from. Sure, it's meant for hunting, but a mobile chair blind is WONDERFUL for photography. It's dang comfortable too, even with cupholders! There are many times where I'll go past a rocky shoreline or wetland and see ducks, shorebirds, wading birds, or other birds scatter as I approach. I'll take the chair blind out, set up next to the shoreline, pull the cover over, and wait. Without movement, without birds seeing a human form, they quickly forget there's a human presence in the area. Just as with the permanent blind, wild and normally very shy birds will often approach within mere feet of your blind. I've even had birds land on the blind and starting singing from the top of it as I sat inside! A mobile blind can be a great investment for a birder and bird photographer.

Your car! - Probably the most overlooked bird photography tool is your car. Many species of birds feel threatened by a visible human presence, but will readily tolerate the close proximity of cars and trucks. As with the use of any blind, using your car as a blind will require patience. Driving right up to the edge of a wetland, for example, is likely to scare off any bird that's close. Don't give up however. Open your window, get your camera ready, and wait. You'd be surprised at how short a wait it sometimes is. Many birds will easily accept the presence of a nearby parked car in their area, and will start to behave normally after not sensing a human being for several minutes. I have many, many photographs taken from inside my car, and many, many more hours sitting there, simply enjoying birds behaving naturally while I sit in close proximity.

Remote Triggering

Are you still having trouble getting close to birds? Well, keep in mind that its not YOU that has to be close to the bird, it's the camera itself! Remote triggering of your camera often allows you to photograph natural behavior that you'd never be able to photograph if you were actually present. Remotely triggering your camera could mean using a corded shutter release, an infrared cordless shutter release, or a remote triggering mechanism that automatically fires when motion is detected in the camera's viewing frame. For me? I have software on my iPhone that allows me to see what my Canon 70D is "seeing", and I can trigger the shutter from my iPhone! This can be a great tool around feeders and other situations where birds repeatedly use the same perches and feeding locations. Simply set up the camera and the remote triggering mechanism, retreat to a safe distance, and wait. I'd suggest a cold Blue Moon (with orange, of course) and a baseball game on the couch, while you periodically check your iPhone to see if there are any birds in front of your camera. Now THAT's some relaxing bird photography!!!

|

| Prairie Warbler, attracted by taped call |

Use of Taped Bird Calls

By 2007, I'd already been birding and taking photos for several years. My photography was much improved from when I started, yet I was still having difficulty getting close enough to birds to get great shots. In June of 2007 a Prairie Warbler was reported nearby, an incredible rarity for South Dakota. Not expecting much of a chance to actually get a photo of it, I went searching for it and did see it from a distance. Another local birder I knew approached and asked "would you like a closer look"? He pulled out a cassette tape (yes...a tape...NOT an iPhone or anything like that "way back" in 2007!), pushed play, and the sound of a recorded Prairie Warbler song started playing through his little external speaker around his neck. Within 3 seconds, that mega-rarity Prairie Warbler was 20 feet away, singing to beat the band, in plain view.

I got a number of good, very close photos, such as the one shown in this section. It was incredible at first, seeing the power of this new tool, playing bird songs to get birds to come to YOU, instead of trying to use blinds or other means to move YOURSELF closer to the bird. I found CD's that had recorded songs of several hundred North American birds, and put them on a little iPod, connected to a very small portable speaker. Now I could play the songs of most bird species in an attempt to draw them closer! It didn't work all of the time, but there are MANY occasions where the use of a taped bird call will bring in a bird to extremely close range.

A tremendous tool for bird photographers, right? Sure. But I rarely use that tool anymore, for two reasons. First of all, look at the photo of the Prairie Warbler in this section. Does that look like a naturally foraging or singing bird? No...that Prairie Warbler is one PISSED OFF, or at least agitated, bird. He heard a rival, and responded in kind. The more I used taped calls, the more I realized that the photos I was getting simply didn't look as natural as photos I got through other means. You have a lot of photos such as this Prairie Warbler photo, a bird in an unnatural looking pose, with a gaze directed right at the photographer. That simply isn't what I'm trying to represent with my photographhy.

The second reason I rarely use taped calls anymore is simple...it's potentially harmful for the bird. There are plenty of stories out there about the intended subject being EATEN by a marauding Cooper's Hawk or other raptor that ALSO was attracted by the song of a singing bird. Having that mega-rarity eaten right before your eyes may make you think twice about using taped calls! Even if it doesn't put a bird in mortal danger, it DOES disrupt a bird's natural routine. Instead of spending precious energy foraging, roosting, or courting, they're wasting it responding to a fake bird call.

I'm dismayed when I go birding now, in that it seems like EVERY birder and photographer has an electronic device they use to play bird songs. As I said, it IS a great tool for getting a bird to come close to you. I'd strongly advise using this tool sparingly though, for the reasons provided above.

Attracting Birds with Feeders

Finally, an extremely effective way to get close enough for great bird photos is to give them some food! Feeder photography is a TERRIFIC way for a beginning bird photographer to get wonderful, close shots, and to practice his or her new hobby. Birds that come to feeders are often used to a human presence to begin with, and are less apt to flush as you take photos. Couple a blind with a feeder and you really have a winning combination. That "blind" could be as basic as shooting out a window from your house as birds come to a feeder. You generally don't want to shoot THROUGH a window, as the extra panes of glass will degrade your image quality, but sometimes I'll open a window by my feeders and take the screen off, giving me unobstructed photo opportunities for birds coming to my feeder.

One problem with feeder photography is that you're capturing an image of a bird at a man-made object, the feeder itself. If your goal is to capture natural-looking images, that's not ideal! Pay attention to how birds approach your feeder, however. For me, I have a crabapple tree and fruiting mountain ash tree on two sides of my feeder complex. When birds approach my feeders, they often will land in one of those trees first, checking for danger, before going to the feeder itself. Getting a photo of a visiting bird in your beautiful flowering crabapple certainly beats a photo of that bird munching on sunflower seeds in your feeder! Knowing your quarry and understanding their general behavior can get you some great, natural-looking photos, even in feeder situations.

Obviously feeders won't work with every species. You're not likely to attract a Bald Eagle to your feeder! Even for birds that WILL eat commonly offered food items at feeders (e.g., suet, sunflower seeds, niger seed, etc.), some are quite comfortable attending feeders while others shy away from feeders. Even if you can't attract every species you want to photograph, having an array of offered items at your feeders can attract a very nice variety of birds. I have one concentrated feeder area where I offer multiple items. Depending upon season, here's what I offer, and what may show up at feeders in my area:

- Main feeder - Black-oil Sunflower seeds (MANY species will come for black-oil sunflower seeds)

- Suet feeder - (Woodpeckers in particular, but also many other species)

- Fruit/jelly feeder - Orioles, Catbirds, Finches

- Nectar feeder - Hummingbirds, but others will surprise you, such as Orioles

- Peanuts - Blue Jays love these, as do woodpeckers.

Again, if you're just starting out, think about using feeder setups to practice your new hobby. Here's a page that describes what you can use to attract different species.

THE ACT OF SHOOTING - CAMERA SETTINGS

It's obviously difficult to provide specific advice on camera settings that would cover every bird photography situation. I can offer some general advice though and insight as to how I normally shoot.

|

| You need to balance ISO, shutter speed, aperture |

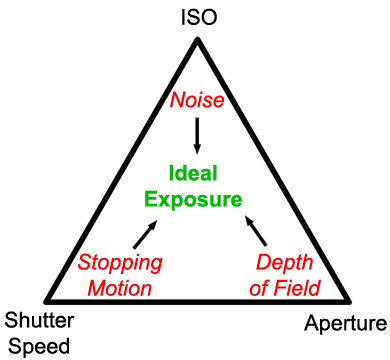

EFFECTS of APERTURE, SHUTTER SPEED, and ISO

No matter what DSLR you're using, you're going to have several camera "modes" to use. This ranges from "full automatic", where the camera itself decides the proper aperture, shutter speed, ISO level, etc. for a shot, to full manual, where the photographer must select each parameter themselves. There are also specialized modes on many cameras such as "portrait", "Landscape", "indoors", etc. where the camera pre-determines specific parameters based on setting or subject matter. What it all boils down to in the end...the camera mode and choice of settings is meant to balance any tradeoffs between aperture, shutter speed, and ISO (see exposure triangle image). A bit about each component:

- SHUTTER SPEED - Shutter speed controls how long your shutter is open. The longer your shutter is open, the more chance your subject has to move. If the subject is moving while the shutter is open, your photo may very well be blurry. In short, shutter speed controls your ability to "stop motion". The faster the shutter speed, the less time the shutter is open, and the less likely your image will have motion blur. A rule of thumb to avoid motion blur when hand-holding a photo...shoot at a shutter speed that is the INVERSE of your focal length. Explanation? This means...for my Canon 400mm lens, to be able to hand-hold a shot, I need a shutter speed of at least 1/400th of a second (in general).

- APERTURE - Aperture determines how wide the opening is that lets light into your camera, once you press the shutter release. Aperture controls Depth-of-Field, which is the focal depth of your image that will be in focus. How does aperture affect that? Aperture is set with "f-numbers" on your camera. the bigger the number, the smaller the aperture, and the smaller the aperture, the greater the depth of field. For example, if I'm shooting a single bird at moderate range, a low f value of something like f/5.6 may be good enough to get all of the bird in focus. If the bird has buddies, with some birds closer to the camera than others, I'll need more depth of field to make sure they're all in focus, so I'll increase the f-value...maybe something like f/10.

- ISO - The concept of "ISO" is similar to what it was with old film cameras. With old film cameras, you could use a "faster" film that had a higher ISO value, if light conditions were low or if you wanted to ensure you "stopped action" and avoided motion blur. ISO for digital cameras controls the sensitivity of the individual pixel sensors to light. The higher the ISO value, the less light is needed for the sensor to record an image. The tradeoff? Noise. The higher you set the ISO level, the more likely it is that you'll have a grainy, noisy-looking photograph.

TRADEOFFS - ISO, Aperture, and Shutter Speed

Looking back at the exposure triangle diagram, the "ideal exposure" for each individual photograph requires balancing ISO, Shutter Speed, and Aperture. In an ideal world, you could always have low noise, a very high shutter speed to "stop motion", and a small aperture to ensure everything in your image is perfectly in focus. In reality...changing the value of one of the three triangle components will affect the other components. For example...when I increase the f-value of my aperture...say, going from f/5.6 to f/10...the opening that lets light into the camera is smaller. With less light, the sensor needs more time to gather enough light to take a photo. Choosing a deep depth of field by increasing the f-value for your aperture thus comes at the cost of a slower shutter speed, potentially compromising your ability to "stop motion". ISO can compensate for that, but again, at a cost. If you need both high depth-of-field AND a high shutter speed, you can increase the ISO substantially, say from the lowest ISO 100 value to ISO 1600. By doing so, the sensitivity of your camera sensor is higher, and less light is needed to record an image. As a result, you can potentially increase BOTH shutter speed and aperature. The downside...as you increase ISO, you progressively increase grainy noise in your image.

Everything comes at a cost when shooting, and you have to learn to balance ISO, aperture, and shutter speed to achieve the desired exposure for your particular shooting situation. Experience is the best teacher, but a little bit about a couple of shooting situations and how I would handle them in terms of balancing these three exposure components.

BRIGHT SUNNY DAY, SUNLIT BIRDS - If you ignore the fact that bright, mid-day light tends to make for rather harsh-looking bird photos, this is the easiest situation to handle. You generally have plenty of light to work with. Obtaining enough shutter speed to get a sharp image likely won't be a problem. With so much light available, you can potentially:

1) Lower the ISO setting, decreasing the sensitivity of the sensor to light. Why would you do this? The lower the ISO setting, the less "noise" you have in your image. With plenty of light at your disposal, there's no need to use high ISO settings. Lower ISO down to a low value...possibly all the way down to ISO 100 if you really have a lot of available light. You'll still likely have plenty of shutter speed, and the very low ISO setting will give you a buttery-smooth, noise-free image. W

2) Increase depth-of-field by narrowing the aperture - Narrowing the aperture (thus increasing the "f' number, such as going from f/5.6 to f/8) will decrease available light to the sensor, but it will increase how much of your image is in focus. You don't HAVE to increase DOF. If you have a single bird and you want a blurry, out-of-focus background, then you'd want a wide-open aperture even if you do have a lot of available light. But in bright, sunny conditions, note that it becomes much easier to shoot at narrower apertures and capture images with higher DOF.

CLOUDY or LOW-LIGHT DAY - Bird photography becomes increasingly difficult as available light decreases. In fact, whether its mostly sunny or mostly cloudy often dictates whether I go out to shoot. In low-light situations, it can be difficult to obtain enough light to ensure adequate shutter speeds. In low-light situations, you're much more susceptible to blurry photos, due to the low light necessarily resulting in lower shutter speeds. How do you counter-act the effects of a low-light day?

1) Increase your ISO. Increasing the ISO will increase the sensitivity of the sensor to light, effectively increasing the shutter speed (at a constant aperture). Even with a "wide-open" aperture, on my relatively "slow" Canon 400mm 5.6L lens, it can be hard to maintain adequate shutter speed on cloudy days. The only tool that allows you to increase shutter speed is to increase the ISO level. In good light conditions, I generally keep my ISO levels between 100-400. In cloudy or low-light conditions? I may go to 1600 or more for ISO level. Again though, realize that image quality will degrade as you go to higher-and-higher ISO values. Today's DSLRs are getting better and better in terms of providing high image quality at high ISO levels, but it's still an issue. For a "pixel-peeper" like myself who insists on the highest quality of images, the degraded image quality when light is low is one reason why I tend to mostly shoot on days with quite a bit of sun.

2) Use a tripod! Note that I hand-hold almost exclusively. However, low-light conditions are one situation where even I will use a tripod or other means to help stabilize the camera and reduce the effects of camera shake. If you have a static, non-moving bird, you CAN capture a very sharp shot even with very low shutter speeds...IF your camera is rock-steady. That means a tripod or other means of support, rather than hand-holding.

FOCUS

|

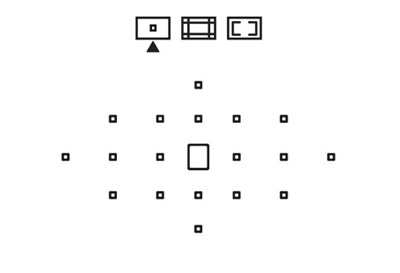

| Focus point array for my Canon 70D |

So far I've focused on the settings of aperture, ISO, and shutter speed. Focus settings are additional important components of bird photography. Settings will differ depending upon your DSLR, but on my Canon 70D, I have three "area zone" options for focusing. The focus point graphic shows what you see on the camera when selecting focus points. You can choose one point, an "area" of points, or let the camera decide. The options, and comments on each, are:

- 19-point automatic selection - AKA, dummy mode, this lets the camera decide what component of the image will be the primary focus point. Simply put, don't use this mode, as you have no control as to whether the focus will be on the bird itself, or a rock, fence post, or other image element.

- Zone Autofocus - Of the 19 potential focus points on my Canon 70D, this divides them into 5 different focus zones. One uses the 9 points closest to the middle of the frame, while the other 4 zones each use 4 focus points, in different areas towards the edge of the image frame. A better option than the full-automatic focus, but it still doesn't let you precisely control what part of the image will be in focus.

- Single point AF - This lets you choose which of the 19 focus points you see in the viewfinder is the one where the camera will try to achieve focus. Use this option!! A very effective method (and how I almost always shoot) is to select the central point as your focus point. Does that mean you ALWAYS have to have the central part of the image frame as your primary focus area? Heck no! If you follow the "rule-of-thirds" for compositing your image, the bird in your photograph won't be directly in the middle, it will be off to the side a bit. How then do you use the central AF point but achieve a pleasing image that follows the rule-of-thirds? When you shoot your DSLR, you typically press the button down halfway to achieve focus, and to see (through the viewfinder) what your aperture and shutter speed are, based on camera settings and the light conditions. When you see a bird, quickly center the bird in the viewfinder, press the shutter halfway and hold it, and you've achieved primary focus on the bird itself. While still holding the camera shutter halfway, you can then move the camera a bit to get the bird in the desired position in the frame. This will VERY quickly become second nature to you, and even with birds that don't sit still you can achieve focus using the center AF point and then recompose the shot in a VERY short amount of time.

Another element of focus settings is whether the camera continually updates your focus after you press the shutter halfway, or if it considers your focus locked at that point. Here are the options on my Canon 70D, and my comments on each:

- Single-shot AF mode - In this mode, the camera considers the focus to be "locked" once you press the shutter halfway and the camera achieves focus. Thus, if you recompose the shot while still holding the button down halfway, your focus point won't change. That's why the shooting method described above works, with the single-point AF selected. You use the center point to focus, press the shutter halfway, and focus is "locked". Thus, when you continue to hold the button halfway and recompose the shot, your focus point won't change, and the bird will still be in focus even if it's no longer in the center of the frame. This is the mode I use most of the time. For perched and/or non-moving birds, you WANT to be able to completely control the focus point, and hold focus while you recompose a shot.

- AI Servo Mode - This mode is primarily designed to assist you in focusing on a moving object. In this mode, when you press the shutter halfway, the camera still achieves an initial focus. However, if the subject matter, say...a flying bird...is moving, the camera will continually update the focus point as that bird moves. Are you shooting a bird in flight, or a bird that is otherwise moving around? AI Servo Mode will likely allow you to "track" focus better than if you use single-shot AF mode. For me? I anticipate whether I'm shooting a bird in flight, or whether I'm shooting a bird that's sitting still. If I'm trying to get a flight shot, I'll set the focus to AI Servo Mode. If I'm trying to shoot a still bird, I set it to Single-shot AF mode.

- Full Automatic - In this mode, you let the camera decide whether to use single-shot AF, or AI servo mode. I rarely use this, as I want total control of the focus mode while I shoot. However, if it's difficult for you to anticipate whether you'll be shooting moving or static birds, or, if you're simply not comfortable yet in switching between the shooting modes listed above, then the full-automatic AF mode may be your best option.

OTHER SETTINGS

While there are other settings you can adjust, the last one I typically worry about is the "Drive Mode". The "drive mode" sets whether you're shooting a single photograph, or whether you want to take a rapid series of photos in quick succession. Here are the options (on my Canon 70D) and recommendations:

- Single Shot Drive - In this mode, the camera assumes you're composing and taking one photo at a time. In other words, to take a photo, you must press the shutter halfway down to achieve focus and then fully press the shutter to take the photo. Do you then want to take another photo? You'll have to again press the shutter halfway, then press it completely to get a second photo. This is the mode I use most of the time.

- Continuous Drive - In this mode, you may press the shutter halfway down to achieve focus and derive your camera settings, but once you press the shutter all the way down and hold it, the camera will rapidly shoot images, as fast as the camera will allow. On my Canon 70D, there's a "high-speed" continuous drive, which takes about 7 photos every second, or "low-speed" that takes around 3 photos every second. Are you shooting a moving bird? Continuous drive mode can be GREAT for birds in flight or for birds that are moving. One BIG advantage to digital...you don't pay for image processing for every image you take, like with film! Don't like the photo? You simply delete it! With continuous drive mode, you can VERY quickly take a series of dozens of photos, but then you can simply delete the ineffective shots. With a moving bird, this mode is great because it captures a range of poses for the bird. In one quick series of shots using continuous drive, you may have some photos where the bird is in a pleasing pose (parallel to the camera, or facing the camera), and others where the bird may have its back to the camera or its head is facing away from the camera. Continuous Drive lets you capture many poses of a moving bird, in a very quick fashion. After you're done, you can then casually page through the different photos and delete the photos that you don't like.

There are less important settings when shooting birds that I won't get into here. Selecting focus point, aperture, shutter speed, ISO, drive mode, etc., as outlined above, will cover you for most bird photography situations. I only have one more piece of advice for bird photography...

|

| Swainson's Hawk - Always be ready! |

BE PREPARED!!!

To conclude, always being prepared will help to ensure that you don't miss that shot of a lifetime. You can generally be assured, for example, that your only chance to get a great photo of a rare species will be when you're not paying attention, you don't have the right equipment for the situation, or you simply don't have your camera with you. Even the simple drive to work in the morning can sometimes provide opportunities for some great photos. I work at a USGS facility 10 miles outside of town, so my drive to work is probably different than most people's. I can take gravel roads to work! I have learned to always have my camera with me, because you just never know whether some raptor might be hanging out on a fence post outside of town, a huge flock of migrating Snow Geese might be feeding in a nearby corn field, or some rare migrant might be seen roosting in a tree on the side of the road. The photo shown in this section of a Swainson's Hawk sitting on a post was taken out of my car window, on the way to work one morning. A gorgeous and very cooperative bird, and a photo I would have never gotten had I not been prepared, and had my camera equipment with me!

You can't get a great photo without being prepared to take advantage of opportunities as they arise!